Dear readers, (OR dear LISTENERS: If you’re a multi-tasker and would rather listen to this newsletter while doing other things, grab your headphones and click the ‘PLAY’ button below. )

Stereotypes often have some truth to them and the more benign ones CAN be funny. I prefer mine to be about pizza and pasta, rather than Mafia-related. So maybe I, and thousands of other Italians, shouldn’t have been offended by the most recent cover of the Economist comparing the UK’s political implosion to Italy, with the words ‘Welcome to Britaly.’

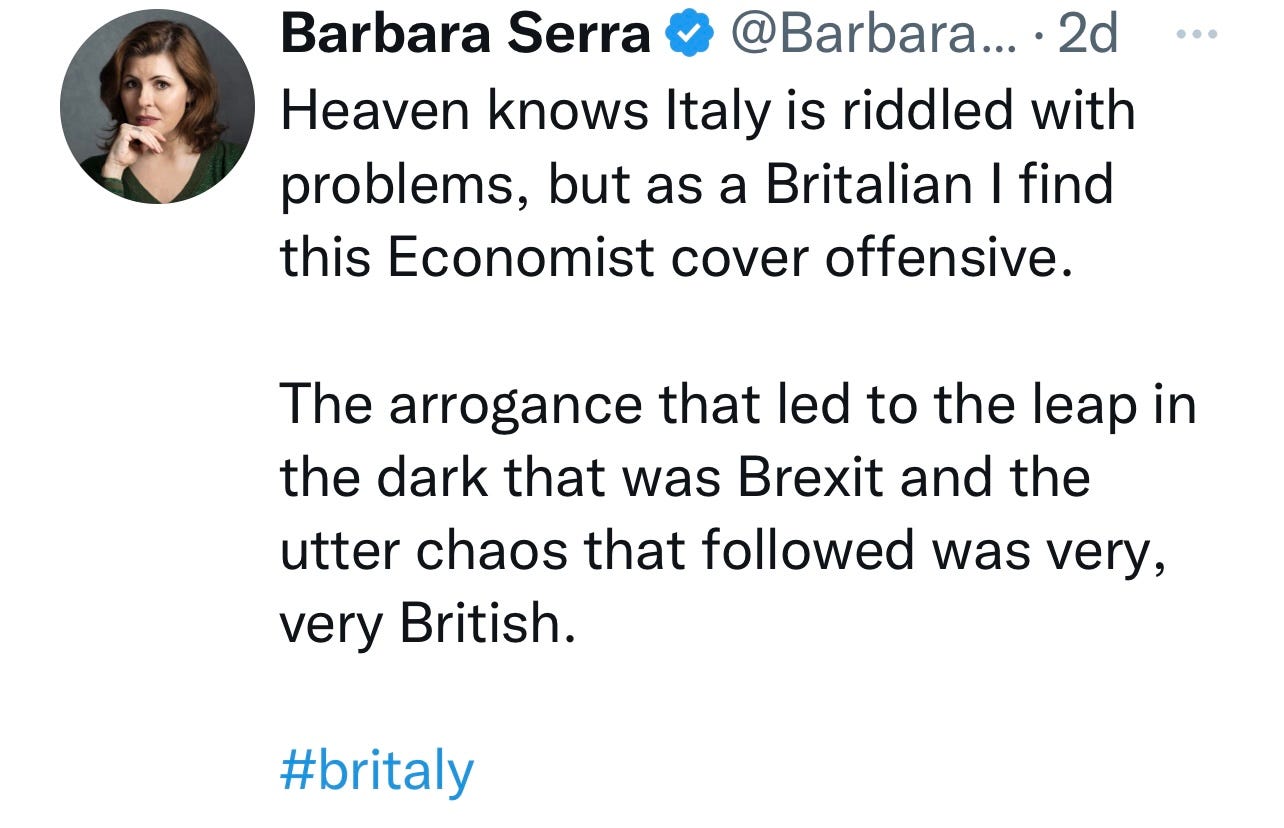

Scroll down to take a look at the cover in question for yourself and let’s kick off proceedings with a cheeky poll:

As is often the case, the article itself is much more nuanced than the cover would suggest.

And while The Economist briefly became the focus of passionate Italian online fury (and there goes another stereotype ;)) it was hardly the first publication to make the comparison. A few days before, The Telegraph published a very detailed piece claiming that Britain’s transformation into the new Italy was now almost complete. And Gillian Tett of the Financial Times made similar comments on Channel 4 news, saying the UK had become like Italy in terms of financial risk and political instability… but sadly without the good food, sunshine and glamour. (Thank you Gillian. We do like a bit of glamour.)

So here are the similarities between Italy and the UK:

Stagnant economic growth

North/South divide, although it’s the other way around in Italy

A low birth rate and an ageing population

Creaking infrastructure

Vulnerability to the financial markets

Political instability

Italy is notorious for its sixty-nine governments since WW2, with an average lifespan of thirteen months. Though it must be said that thirteen months sound like an absolute age compared to Liz Truss’s forty-five days in office.

So if the comparison is valid, why was I offended?

Having lived through the post-Brexit period as an EU citizen in the UK, I felt the comparison and narrative had a big omission, because it didn’t address the very BRITISH reasons of how the UK got to the current political meltdown.

As The Economist points out in its article “the political instability that used to mark Italy out has fully infected Britain.”

But the nature of that instability is very different. In Italy, governments tend to fall because they are made up of fragile coalitions, with small parties playing the part of volatile king makers.

The British situation is inherently different. It is the convulsions of one party which, since the Brexit referendum of 2016, has had to deal with the repercussions of an issue which had been bedevilling it for decades.

This isn’t a throw away line within a wider argument. It’s a crucial difference.

Brexit was a leap in the dark. No one knew what kind of separation the UK was going to have from the European Union. The Conservative party, which has been the only party in power since the referendum, has been making it up as it’s gone along.

Brexit was an ideologically-driven step into the unknown which now, with the benefit of hindsight and the realisation that pandemics and wars can strike when you least expect them to, looks like a spectacular case of national self-harm.

In fairness, many didn’t need hindsight to come to that conclusion. David Cameron himself, the Conservative Prime Minister who called the referendum in the hope of uniting his party over the issue of Europe (oh, the irony…) said before the vote that Brexit would be an act of economic self harm. He called it a “roll of the dice with the future of our children and grandchildren."

Which I think pretty much sums up where we are now.

And that is why the comparison with Italy rankles. Because for all of Italy’s structural issues and instability, the country has never committed a similar act of self-harm.

Plenty of politicians use the EU as a political football to be blamed when things go wrong. But Italy has never seriously considered anything as potentially damaging as leaving the EU, unlike the UK. In my tweet I used the word arrogance to explain in part what was behind Brexit. I thought long and hard before using that word. It makes me uneasy because it doesn’t represent the vast majority of the Britons I know. But it does reflect part of the sentiment that was behind the Brexit decision. The UK has many reasons to be proud of itself. In this case, misplaced pride came before the fall.

So, welcome to Britaly? No, Economist, let me fix it for you.

Welcome to Brexit Britain.

On the bright side, while British politics has been imploding, Italy has elevated politicians who are openly nostalgic for the country’s fascist past to some of the highest positions of public office.

So, you know, things could be worse.

Thank you for reading News with a Foreign Accent. Please leave a comment below if there’s anything you’d like to add, and remember that paid subscribers can always send me a direct email to barbaraserra@substack.com - I love hearing from you and will strive to reply within 24 hours. Please make sure you’re sending it from the email account you used to register to this newsletter.

Chat soon,

Barbara

👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏.

Just one doubt...Does Britain really have a low birth rate? It definitely doesn't look like in the Medway area where I just moved out from. At least not in comparison to Sardinia where I'm back staying...not many babies around

The trouble is that there are far too many old farts in the media in this country.

That kind of naff humour (topped off in this case with casual offensiveness towards another country), like the supposedly funny-for-not-being-funny "puns" you get every day in the unspeakable British tabloids, shows only too embarrassingly the age and cluelessness of the cartoonist.

Above all, however, it shows how crap, ancient and undoubtedly little Englander the editorial team at The Economist are. The Economist has supposedly built up a rep for being "the best in the business" for economic analysis for decades. I've long been sceptical about that.

Judgement in such matters as "what's funny as opposed to crap" and "gratuitous insults based on national stereotypes a 12-year-old would avoid" counts and reflects wider judgement. One down for The Economist.