The barriers faced by second-language English journalists

I'm sick of lying to young foreign journalists who ask me for advice. Because the only honest reply is: "Can you pass as a native speaker?"

This article will strike a particular chord with those who, like me, are second-language English. But for all you native speakers about to click away, don’t. I’m highlighting a blind spot that anyone who cares about true diversity in media should find valuable. After all, there are more than 1 billion second-language English speakers in the world. It might help you to know what they’re thinking.

I’ve also recorded this newsletter, so if you’d prefer to listen to it rather than read it, please click below.

It is strange that at a time when the issue of privilege is finally being widely discussed (be it white privilege, male privilege, class privilege etc…) one of the biggest privileges of all hardly ever gets a look in, namely:

The privilege of language or, more specifically, the privilege of speaking English.

It may sound like an odd concept if you’re reading this in a country where English is the official language, like the UK, USA or Australia. But English is much more than the spoken language of the Anglophone world. English is the conduit that allows our world to be as interconnected as it is.

From social media to business, journalism, research, academia, the entertainment industry and everything in between, English is the key needed to access our globalised world.

Since English is the global language, it’s not surprising that more than a billion people have learnt it as their second or third language. But it’s the 600 million or so native speakers who have really hit the linguistic jackpot - with added bonus points if their words come in a clear, posh-but-not-too-posh British accent.

Speaking English as your native language is a massive privilege that will help you cement your status in almost every field. And yet it’s very rarely acknowledged as such, especially by native speakers themselves.

I guess that’s the whole issue with privilege: If you have it, you don’t see it.

In the case of language, if you have it, you don’t hear it.

This is where journalism comes in, and my so-called lived experience. Because nothing has had more of an impact on my career than my voice or rather, my accent. I learnt English at the age of 9, when I moved from my native Italy to Denmark and attended the international school in Copenhagen. I have very clear memories of not being able to speak English, of walking into that classroom and not understanding a single word anyone was saying. That sense of ‘otherness’ and alienation is seared in my memory and I’m sure it’s shaped me in more ways than I realise.

I learnt English quickly, as children do, but I don’t think I was a confident speaker until my mid-teens. As my proficiency grew, I also developed that rootless, mid-Atlantic accent which might as well be called ‘International School English’.

So I now inhabit this strange world where native speakers can tell English is not my mother tongue while ‘foreigners’ think I sound like a native speaker. All I can say is that I’ve been working on my voice every single day since becoming a journalist. What you hear now is not what I used to sound like. I work hard on clarity, diction and intonation though I refuse on principle to put on some faux-posh accent. I am no English Rose and I don’t see why I should pretend to be one. But I have never voiced a report, presented a news bulletin or done a live interview without being acutely aware of my English.

I have dozens of little tricks I employ before going on air to anchor my voice. And I berate myself whenever I slip up on pronunciation, because I know that mistake will lose me credibility. My 20 years’ experience in English-language media tells me that.

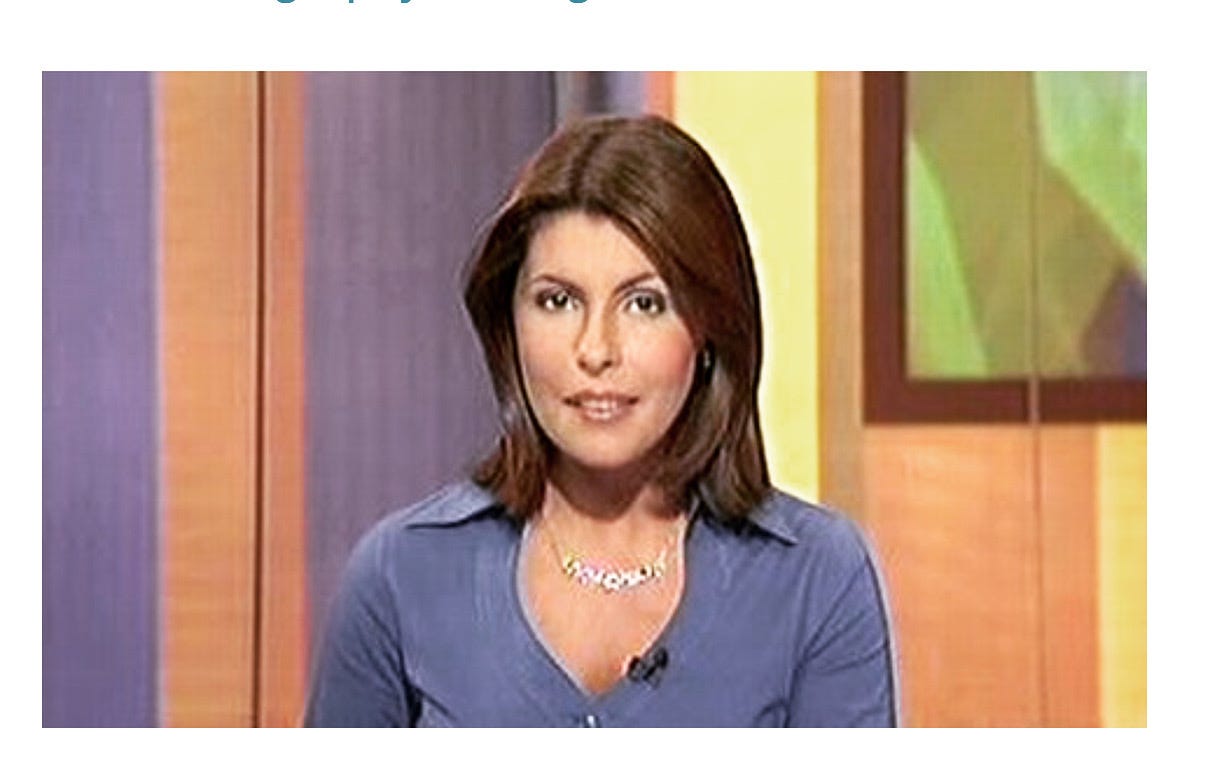

One of my claims to ‘fame’ is that I was the first non-native English speaker to present a flagship news programme on British terrestrial TV when I was a FIVE NEWS presenter between 2005/2006. I had previously cut my teeth as a Sky News reporter and had done a few presenting shifts at BBC London as well. I had a wonderful time in all those networks, but my foreign accent was always an issue. I’ll write about that in more detail in the future. Let’s just say it was not smooth sailing. And that I realised early that ‘diversity’ did not apply to what made me different.

Then came the move to Al Jazeera English in 2006 and as you’d expect, things were a little more relaxed on an international channel with a global audience. But if you really listen, you’ll find that even on International networks, native speakers dominate.

Diversity rarely extends to second-language English voices.

Over the years, I’ve been contacted by many young journalists asking for advice, especially those who, like me, aren’t native English speakers. If you can see it you can be it, goes the adage. Or in this case, if you can hear it. And I was often the only voice they’d hear on air that sounded ‘odd’, as a colleague of mine once so eloquently put it.

I never really had a mentor when I was starting out, so I always try to find the time for a chat, however brief.

But ultimately, I got sick of lying to them.

I can talk to young journalists about ambition, curiosity and hard work, but there’s one main thing I need to know, one thing that will make the biggest difference to their career. A question I have the answer to within the first 30 seconds of any conversation. And that question is: “Can you pass as a native speaker?”

Because if you can’t, any kind of broadcasting career will be much harder for you, and you will probably never be considered for many high-profile presenting jobs.

Actually, let me qualify the ‘never’ in that last sentence. When I first started training as a journalist, a senior editor (who I think was trying to be kind and whose honesty I appreciated) told me “You will never broadcast for the BBC.” As it turns out, my TV news presenter debut was on BBC London. Then again, I was also taken off air a few months later because of my foreign accent, even though London is one of the world’s most cosmopolitan cities. So I won’t say ‘never’ but I’m not going to soften the blow: It’s going to be an issue. Very few managers will actually say this to their foreign-sounding aspiring broadcasters because it’s a minefield, easily offensive, potentially discriminatory or maybe because they simply haven’t thought about it properly. It’s a sensitive subject. Nothing quite like the way we speak is as tied to our identities, our roots, our essence of self. So the problem is never identified, and therefore it’s never addressed. If you don’t believe me, well, just listen.

How many second-language English voices do you hear on mainstream TV? Or radio? Or podcasts for that matter? You can count them on one hand. I know that because I actually have counted them. The very, very few exceptions do not make the rule.

This is a big subject and we need to differentiate between domestic and international channels, correspondents and presenters, reporters who work on domestic news as opposed to international stories. But the native-English issue is present EVERYWHERE and not even international channels are exempt. In fact, years ago I was told what the ‘formula’ was for international news presenters. It’s offensive but painfully accurate, and I will save it for the next newsletter.

So for now let’s focus on domestic British news. The last census showed that a sixth of residents of England and Wales are foreign born - in London that figure rises to 40%. Now, you can be foreign-born but have moved to the UK as a child and speak flawless English anchored in a British accent. Remember the test - can they pass as native speakers? And if they can, I’m sorry, to me that doesn’t really count. If a culture has had enough of an impact on you to affect the way you speak, it’s had enough of an impact to affect the way you think. That’s why this matters. Diversity isn’t just about fairness. It’s about making the product, in this case journalism, more representative. If the UK has so many foreign-born residents and citizens, its media should reflect that, and not just showcase the ones that don’t stand out.

I wish things had changed significantly from when I started out in journalism, but the young foreign journalists I speak to tell a different story. Some are starting to speak out, like the native French/UK resident Camille Dupont. Camille wrote an incisive article denouncing the lack of EU journalists in British newsroom and highlighting that non-native speakers can also write well in English. She’s spot on about the lack of EU journos (I’d written about it in a previous newsletter. There’s 5 million of us in the UK and it’s like we don’t exist). Camille highlights that non-native speakers can and often do speak English to the necessary level for a career in journalism.

I agree with her, but there are other issues too:

Perfect mastery of language is a non-negotiable skill in journalism. Words are our tools. Writing a powerful and concise TV script to strong images is akin to poetry. Most people can’t do it in any language, and doing it in your second language is harder. Not impossible but harder. There is no shame in admitting that. Helping non-native speakers develop their language skills should be seen as a key part of training if a network is serious about diversity.

But to me the bigger issue is what language represents: a cultural link to the audience you’re speaking to.

A deep knowledge of the country you’re reporting on, the customs and habits of its people, their culture, their history, their pride and their hidden shame, their sense of self. You have to connect with your audience.

When I was a reporter in British newsrooms I used to dread the sudden celebrity deaths. It was usually some entertainer from the 80s or 90s who had shaped a generation’s childhood and that I, not having grown up in the UK, had literally never heard of. People would be welling up around the newsroom, collectively reminiscing about this person’s legacy while I’d be furtively googling his/her life on my way to the edit suite to package something suitably emotional about someone whose very existence I had previously ignored.

It may sound trivial but it’s not. The audience can always spot a fake, and that’s what I felt like in those situations. An imposter. Because it was a glaring example of the main barrier that foreign, and foreign-sounding, journalists will face:

News is about TRUST, and trust is tribal.

If you sound foreign, you are by definition not part of the tribe. Every word you utter ‘others’ you. The beauty of multiculturalism is that you can be British regardless of race, religion or heritage. Many Britons of ethnic background rightly get offended when they’re asked ‘where they are from’. But a foreign accent is the proof that someone actually is from somewhere else. That they were shaped by another culture. I’ve lived in the UK my whole adult life but it would be unreasonable for me to get angry when asked that question. My voice is proof that I was not born here. And this matters when it comes to news.

I always think that if I’d stayed at Sky News instead of moving to Al Jazeera back in 2006 I probably would have done a stint as Sky’s Europe Correspondent. But can you imagine if a main British TV Network had had someone audibly foreign reporting on the Brexit negotiations from Brussels? Forgive the cynicism, but I don’t see that happening. The us-and-them dynamic is real, and a portion of the audience simply wouldn’t have trusted my loyalties. And I say that as someone who’s lived in the UK as a foreigner for nearly 30 years. But I would not have been seen as being ‘one of us.’ My foreign-sounding last name wouldn’t have been the obstacle. But my foreign voice would have othered me with every single word.

I hope I don’t sound defeatist, and to all the young foreign journalists who are reading this, please know that I hope my experiences will be to your benefit. I think things ARE changing, and that they’re changing in your favour.

But the main driver of any change is realising there is an issue in the first place, and trying to change it together. That’s why I’d like to use this newsletter to share the experiences of other ‘foreign’ journalists, in the UK or in any part of the anglophone media.

I’ll be featuring some here, and chat to them on the podcast feature. but please do reach out or nominate anyone that you think has an interesting story to share in the comments section below, or in the Substack Chat feature that you can find on the Substack APP.

I’ll leave you with a quote from a song that always helped me when I felt particularly alienated. Ironically it’s Sting’s ‘An Englishman in New York’ - because, guess what? Everyone is a foreigner somewhere.

The first time i walked into Aljazeera's newroom, my editor took me around to meet the rest of the team. She introduced me by name and then went on to say: "isn't she great, an Italian speaking with a cockney accent?" I guess that came as a bit of a shock to me. I had never felt nervous about how I might sound to an english speaker... but suddenly that remark made me feel extremely self-sound- conscious! Forget the Italian, it was the COCKNEY word that got me. Ever since, I make sure I pronunce T for T and F for F ...and most of all ...that, if anything, i sound more Italian than Cockney :)

Thanks, Barbara, for writing this article! It's a great read, and I've enjoyed reading it. You raised very pertinent issues. When I worked for AlJazeera (was web editor), I was approached by African journalists who had worked in Africa as TV presenters, and they wanted to know if they could work as presenters for AJE English. I would help them send their resumes to newsroom managers, but I was only trying to be polite because I knew perfectly well that the English they spoke, though very good by the standards of their countries, was never going to be accepted by hiring managers. I was the only web editor from Africa, and in my time at Al Jazeera, I saw only one woman from my country hired as a producer. She grew up in the UK and studied there―and speaks English with a British accent.